Elvis (1956) and All-Star Squadron 50-52

The Ramble

This week's Ramble is pretty much all personal nonsense that you can skip if you just want to hear my opinions about Elvis and/or comics. Next week I'll write a review of something fun.

First I'd just like to apologise for this newsletter missing a week. Last week I had to make an international flight, get a podcast episode out, and do my taxes, any two of which I could have coped with while still getting a newsletter out, but three was a bit much on top of the continuing international situation.

Speaking of my taxes, I said in the last newsletter that I would be setting up a pay option for this newsletter at some point. I will, but it's not live yet. Stripe, who do the payment processing for ghost, the newsletter provider, insist on having a "customer contact number" that gets shown on the bank statements of any paid subscriber. As I'm not keen on giving out my personal number to all and sundry I'm going to have to obtain a burner phone before I get that done. Watch this space...

So last week was a bitty week. But that bittiness is, I suppose, appropriate for what looks like it's going to be a very bitty year. Now I'm back home, my 2025 is officially properly starting, and if everything goes to plan it's going to be a year with a multitude of creative outlets for me. There's the podcast of course, which will always be my primary focus, but as I said last week, working on other things actually gives me much more energy for the main podcast, and one reason things have gone slower recently is that I've needed other outlets for my creativity. So this year I've got several irons in the fire, half of which won't actually come off, but that's the way these things work.

But here's the plan for what I intend to do (other than releasing volume three of the book series based on the podcast and, hopefully, finally getting out of the sixties in the podcast – there are thirteen songs left to cover, and at my current rate of just under one song a month that seems optimistic, but songs 184,185, and 186 were planned as a trilogy before I started this multi-part thing – all are records on the same label, with the same producer, and one of the songs is actually about the artist of one of the other songs – so I'll probably cover all three songs in just four or five episodes rather than each of them having two to four).

Most excitingly for anyone who likes my podcast, which I assume is about 99.9% of you, I'm planning a spinoff miniseries of sorts. A friend of mine (a well-known creator in her own right) had an idea for a podcast about a non-musician figure who was very entangled in the lives of some musicians, and whose story is going to come up a little in the main podcast this year. She thinks it would be fun to explore this individual's life, so we're going to do a little four-part miniseries in a more chatty, lighthearted, vein than my work normally is, but which will definitely be of interest to anyone who enjoys the stories I tell. It's going to be more the kind of thing that gets put on those Guardian best podcast lists and stuff, more of a wide-audience thing than my more intense work, but definitely in the same area. And handily that one will be able to reuse a lot of research I've done for the podcast.

Things are also moving, very slowly but definitely, on a documentary film I'm co-writing with a well-known musician turned filmmaker. That project is his baby, and he's going to direct it, but it looks like he's getting his ducks in a row regarding funding and it may go into production this year. That film will be on sixties music and so again will be me reusing things I've already done for podcast research. I won't be able to announce anything about that until it's announced, because I'm not the main driver of that project.

I'm also going to work with the wonderful genius cartoonist Fraser Geesin on a second volume of our little chapbook series Tales From 500 Songs. We did a volume of this a couple of years ago to sell at the Thought Bubble comic convention – it's basically ten of Fraser's humorous illustrations of events I've talked about in the podcast, with me providing lighthearted one-page summaries of the things he's illustrating. My $5+ Patreon backers got a digital copy of volume one when that came out, but if you didn't get it at the time you can buy a PDF of it from Fraser for £1 at https://www.frasergeesin.com/digital-comic/tales-from-500-songs (and while you're there, buy some of his other stuff – he's great). Hopefully we'll have volume two done in time for Thought Bubble this year. Fingers crossed.

Incidentally, you can buy a couple of Fraser's drawings for these projects – Herman's Hermits as a death metal band, and Rod Stewart crying at being told he can't be in your band – as various bits of merch from the 500 Songs merch store at https://500-songs.teemill.com . (Don't worry, I won't be constantly spamming you with commercials for my stuff in this newsletter, but I also think I haven't really told enough people that the merch store is even there).

And also I've been playing with MuseScore, which is the first bit of Linux music software I've ever come across that seems to actually work, and to be relatively intuitive to use. I'm very cautiously thinking about recording an album, the first proper music I've made since 2007, when Tilt and I made a couple of EPs. We'll see. It'll have to get past the fact that I am legitimately the world's worst singer though.

Likely no more than half these projects will come off (that list there is in rough order of likelihood, with the podcast spinoff a certainty and the album almost certainly not happening), and again I want to reassure people that none of these can or will take any time away from the podcast, which I spend far more than a normal work week working on every week, and will continue to do so. But right now I'm feeling hopeful at least about my own creative work, if not about the world in general.

And speaking of the world in general, before I leave this Ramble bit, I just want to express solidarity to anyone who is currently suffering because of the abhorrent actions of Trump, especially the trans people his executive orders have been targeting. I wish I could do more than just say "this is wrong," but I can at least do that.

Link of the Week

I've shared this before on my social media and on the podcast website, but new newsletter, new opportunity to link this. Some of you will know Shawn Taylor, who runs the 500 Songs Fan Facebook group. (For those of you who don't, that's an "officially unofficial" group, on Facebook where I don't have an account, where people can talk about my work behind my back with no danger of me seeing it, but which I asked Shawn to run). Shawn is one of my oldest and closest friends – I've known her over twenty years – and about two years ago now she was diagnosed with lung cancer. As she lives in the US, is too ill to work herself, and her husband is retired, this is obviously not great for her financially, and so there's a GoFundMe to help pay her costs at https://www.gofundme.com/f/help-shawn-fight-stage-iii-cancer . I would consider it a personal favour if people donated to that.

(Please don't ask me to share other GoFundMes and so forth here. I will do so if and when it's something particularly important to me, generally someone I'm close to.)

Next week's link will be something fun and interesting like last time, not something depressing like that.

Elvis Album of the Week: Elvis (1956)

Elvis' second album, both of his career and of 1956, simply titled Elvis, is in many ways his first real album. While Elvis Presley was a collection of outtakes from the Sun sessions, offcuts from the "Heartbreak Hotel" session, and filler tracks recorded at one other session to make up a fill album, all with subtly different lineups of musicians, this album was recorded as an album, with only one track ("So Glad You're Mine") a leftover from the January sessions. This time eleven of the twelve tracks were recorded in one three-day session (along with both sides of the non-album single "Too Much"/"Playing For Keeps") and the lineup was consistent throughout – other than Shorty Long's piano on "So Glad You're Mine", the only musicians are Elvis, Scotty Moore on lead guitar, Bill Black on double bass, DJ Fontana on drums, and the Jordanaires.

The Jordanaires were a Southern (white) gospel group, who Elvis had wanted to sing backups on his recordings from the beginning, but only Gordon Stoker, their leader, had been present at his initial sessions because RCA had got in cheaper substitutes who were under contract, a sort of "We have Jordanaires at home" situation. After Elvis kicked up a fuss, they would be his regular backing vocalists on every session until the end of the sixties, and their prominence on his recordings meant that they became the first-call male session singers for every record made in Nashville during that time – if there are male backing vocals on any record out of Nashville from around 1956 to 1970, they're the Jordanaires (if there's a single female backing vocalist, it's Millie Kirkham, who joined the Elvis/Jordanaires team in 1957. If there's a female backing group, it's the Anita Kerr Singers).

The piano on the sessions is either Elvis or Stoker – nobody is quite certain who played on which tracks, as most of the session tapes are lost, but it seems like Elvis played on "Love Me", "Old Shep" and "How's the World Treating You", playing acoustic guitar on every other track, while Stoker played on "Rip it Up" and "Anyplace is Paradise". As far as anyone can ascertain, there are no session players on the album at all, other than Long on his one track.

Artistically, this is to my mind a clear step forward for Elvis' albums. It's a much more confident album than the first one, and surprisingly given the smaller number of instrumentalists it sounds fuller, thanks largely to the contribution of the Jordanaires. But there are two things to note here which are worth paying attention to. The first is the narrowing of the focus when it comes to cover versions of new material – a full quarter of this album is cover versions of one artist, Little Richard, and those three recordings are all clearly inferior covers of much better records (though at this point Elvis was good enough that none of them are bad records, just nowhere near as good as the originals).

The charge that Elvis was doing cultural appropriation and ripping off Black musicians and making artistically inferior covers of their work is, I think, vastly overblown, and is an accusation usually made by people who don't know much about Elvis, the fifties music industry, and the complicated interplay of influences that crossed racial boundaries in both directions (though yes, in ways that definitely advantaged white people and gave Elvis a level of success that Black artists who influenced him could never hope for). But to the extent there's any truth to it, this album is the one that makes the strongest case for it, and that's specifically because of the Little Richard cover versions.

But interestingly, I think if there's appropriation and watering-down going on here, it's not of Richard's Blackness but his queerness. Now, as a cishet white bloke, I'm not the authority on these things, at all, and it's also debatable whether Elvis himself was entirely straight, given the unconfirmed and unconfirmable rumours about some of his relationships – and certainly a big part of his appeal in the early years was a suggestion of femininity and/or queerness about his presence. But at the same time, judging purely on his vocal performances, Elvis is... not uncomplicatedly cishet masculine, because there's often a knowing irony there that's an important part of camp, but certainly comfortably within the normal permitted boundaries of masculine expression. Little Richard, on the other hand, exudes queerness in every single syllable.

And I think people are hearing that gap between Elvis and Little Richard's performances – the gap between mostly-cishet mostly-masculinity and someone who laughs at the single straight line that is the Kinsey scale and lives in some other dimension of sexuality and gender expression altogether – and hearing it as a gap between a white man and a Black man. Which of course it is as well, but I think discourse around Elvis' appropriation of queer aesthetics might be far more... I was going to use the word "fruitful" here and then realised how objectionable that would be coming from me... far more productive than discourse around his relationship to Black music generally has been.

As with last week, I've put a Mixcloud together of original versions of the cover versions, along with Elvis' version of the originals on the album (in the case of "Paralyzed", one of the originals, I'll be substituting in Otis Blackwell's original demo, partly because it means I won't be breaking Mixcloud's rules about number of songs by one artist, and partly because it's interesting to see what Elvis did differently). You can find that at https://www.mixcloud.com/AndrewHickey/elvis-second-album-the-originals/

That won't be something I do as a regular thing, because after this point very few Elvis albums are made up mostly of cover versions. These first two RCA albums see Elvis in transition, from someone who is mostly interpreting songs that have previously been recorded by other people to someone who is mostly recording songs that have been specifically written for him – at first largely by people who know how to write to his strengths, like Leiber and Stoller and Otis Blackwell, and later much less so.

Rip it Up

The album opens with the best of the three Little Richard covers. Elvis' version of this track is quite exciting – if you don't know the original. As on much of this album he's singing much lower than he was on most of the material on the first album. If you only had this record as evidence, you'd assume that Elvis was a baritone – he seems to have set himself a challenge to work in a different part of his range, staying at the bottom of his chest voice for much of the record.

As an Elvis track, this is absolutely fine, but the problem is that Little Richard's track is a track, not a song. Little Richard songs roughly fall into two classes – songs he wrote or cowrote himself, which are often winking nods to queer culture, and songs like this which were written for him by Bumps Blackwell and John Marascalo. Those songs are all bland teenage party things, interchangeable to the extent that even though I've known both songs for over forty years, I was just about to quote a lyric from "Ready Teddy" to talk about this song *even while listening to it as I type".

Little Richard's original works because it literally doesn't matter what Richard is singing, it's the sound of his voice that makes the record. And while Elvis was a great singer, he didn't have the sheer outrageousness of Little Richard's performance to fall back on. This is by no means a bad record, but it's not a great one, and Little Richard's original very much is.

Love Me

After "Hound Dog" (which we'll get to when we get to the first of Elvis' compilation records) was a hit, RCA turned to Leiber and Stoller to provide a follow-up. However, they weren't, yet, particularly keen on Elvis as a performer – they hadn't enjoyed his version of "Hound Dog" at all, and so they didn't want to provide anything new for him.

Instead, they suggested that he record a song they'd written for a duo called Willy and Ruth, one of the many male/female R&B vocal duos that turned up in the mid-fifties modelled on Shirley and Lee, but who never had the success of Mickey and Sylvia, Ike and Tina Turner, or Gene and Eunice. According to Leiber and Stoller's autobiography, "Love Me" was actually written as a joke, "a parody of a corny hillbilly ballad", though the original version is definitely an R&B song rather than a hillbilly song.

Elvis, though, takes the song seriously – or at least he doesn't seem to be mocking it too much, though there's a certain mannered nature to the over-emoting he does at points – and his version is definitely a country ballad. The Jordanaires' backing vocals here are the kind of thing that Neil Innes parodied in his "Elvis and the Disagreeable Backing Singers" (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o1781tC5s7k) , with repetition of every line of the middle eight in the second person after Elvis sings it in the first ("I would beg and steal"/"He would beg and steal"/"Just to feel"/"Yes just to feel") which is a stylistic element that's rather dated now, but it's a great track, and Leiber and Stoller were impressed enough by his performance that they did soon start writing specifically for him, with results we'll see over the rest of the fifties.

When My Blue Moon Turns to Gold Again

This is the first radical reworking of a cover version on the album. The original version of "When My Blue Moon Turns to Gold Again", by Wiley Walker and Gene Sullivan, is a very pleasant mid-tempo Western track of a kind that Gene Autry or Roy Rogers could easily have had a hit with. The song had been a country hit three times over in the forties, and would become something of a country standard.

Elvis' version is taken at a similar tempo, but the addition of D.J. Fontana's drums, playing a simple shuffle, and the Jordanaires singing "ba-da-ba-da" backing vocals, give it a forward momentum that isn't there on the original. Elvis strips down and simplifies the lyric, Scotty Moore adds a fun guitar solo, and the whole thing is a pop record, and a good one.

Long Tall Sally

This, however, is a disappointment. Little Richard's original is one of his greatest records, a wonderfully joyous celebration of transgressive sexuality, coded just enough that it slipped past censors in 1956 (uncle John is, rather blatantly, a customer of a trans sex worker, Sally). Elvis replaces Little Richard's joyous shriek with a gravelly yell, which is effective, but just not as effective, and Fontana's drumming is a bit too four-square (though he plays some nice fills). Scotty Moore is the most valued player here, turning in a great guitar solo that lifts the record.

It's important to note that these Little Richard covers are not bad records in any objective sense. They are, in fact, very fun, enjoyable, examples of early rock and roll. But they invite direct comparison to superior records released only shortly before, and in every case Elvis seems unsure how to handle the material other than just trying to copy Richard's phrasing and hope for the best.

These aren't clueless Pat Boone covers by someone who doesn't like the material. They're by someone who does like the material but doesn't understand why he likes it.

First in Line

This is the first song on the album to be written specifically for Elvis, and is by Aaron Schroeder and Ben Weisman, who wrote seventeen and fifty-seven songs for Elvis, respectively. But there's a reason that Leiber and Stoller, Pomus and Shuman, or Otis Blackwell are, if not household names, at least names recognised by music lovers while Schroeder and Weisman barely get mentioned even in Elvis fan circles.

This is not a bad song, but it's a workmanlike song. The lyrics are also rather outdated for the time period – it sounds like a song written for the Ink Spots repurposed for Elvis, though that's clearly not what happened. It's far and away the most forgettable thing on the album, sounding in this context like an inferior remake of "Love Me", though Elvis' vocal is extremely good (it apparently took him twenty-seven takes to get it right – he was a perfectionist in the studio at this time).

Paralyzed

This, though, is excellent. Written for Elvis by the great Otis Blackwell, who would go on to write "All Shook Up", "Don't Be Cruel", "One Broken Heart For Sale", and "Return to Sender" for him (and who also wrote "Fever" which he would record, and "Great Balls of Fire" and "Breathless" for Jerry Lee Lewis) but credited to Blackwell/Presley because of the Colonel's then policy of getting Elvis songwriting credit on songs written for him (a common practice for singers now and then, but one which Elvis would soon end, because he felt bad getting credit for work he didn't do, though he continued to get a cut of royalties in return for recording songs by new writers).

Blackwell's demo is clearly an R&B song – it sounds vaguely Fats Domino – but Elvis takes it in a more pop direction, and turns it into a wonderful, frothy, pop track, singing in a higher part of his range than on much of the album. The only flaw is a slightly muddy instrumental track – the piano and bass are a bit of a mush down the bottom end, and Scotty Moore's guitar is almost completely inaudible except for the very last note. But Elvis' vocal performance is a delight, and the Jordanaires' vocal arrangement is one of their best.

So Glad You're Mine

This is probably the most radical reworking of any of the cover versions on the album. The original, by Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup (who also recorded the original version of Elvis' first single "That's All Right Mama" and "My Baby Left Me", which had been the B-side to his recent non-album single "I Want You, I Need You, I Love You") is a slow Delta blues and interestingly shares some floating lyrics with "Long Tall Sally" ("My baby Lil, she's built for speed/She's got everything in this whole world I need" compared to "well long tall Sally, she's built for speed/She's got everything that uncle John needs").

Elvis turns it from a Delta blues into an urban rhythm and blues track of the type that might easily have come out on Atlantic records (though Long's piano playing is more country flavoured than anything Atlantic would have put out at this time) with an instrumental build section before Scotty Moore's twangy country guitar solo (another stylistically incongruous element, but it works).

Both tracks are good examples of the type of record they're trying to be – I could happily listen to either pretty much any time – and of all the tracks on this album, this is the one where Elvis gets to show his skill as an interpreter the most. It's a total reworking of the song, far more so than his other Crudup covers are, and we see once again that the less Elvis is modelling his performance and arrangement on someone else's version of the song, the better the finished record. A definite highlight of the album.

Old Shep

This is the song that Elvis had been performing for the longest – he performed it at a talent contest as a pre-teen – and is clearly a song that meant a lot to him. Unfortunately it's a song I can't really listen to very easily, as I'm a dog-lover and it's a song about a beloved dog having to be euthanised after growing up with the narrator. It was on an Elvis' Greatest Hits collection I had as a small child as well, so it hit me emotionally before I could develop any cynicism about such things, and remnants of that remain in my feelings about it now.

I've listened to both this and the Red Foley original precisely once each for this review, and I find the Elvis one, which is taken at a much slower pace, by far the better and more affecting of the two. It's clearly a song which meant a lot to Elvis. It's a great performance. But not a record for me.

Ready Teddy

This is another Little Richard cover version, and you can basically sub in the same things I said about "Rip it Up" here. "Ready Teddy" was the B-side to "Rip it Up", and the two were essentially the same record – you can substitute verses from one into the other with basically no difficulty. Of Little Richard's classic run of singles from "Tutti Frutti" in October 1955 through "Ooh! My Soul!" in May 1958, "Rip It Up"/"Ready Teddy" is to my mind the weakest (though that's a relative thing, as that ten-single run is as good as any in music), and it's a single that relies almost entirely on Richard's performance, and Elvis simply doesn't match it even slightly. Again, a perfectly decent rock and roll record if you've not heard the original, but like all his other Little Richard covers, a record that fundamentally has no reason to exist.

Anyplace Is Paradise

This is, I believe, the third of the songs on the album that were written specifically for Elvis. The song is of some interest, as it's an eight-bar blues that seems to want to be a twelve-bar blues – the second line of each verse seems foreshortened, as if it's rushing to the end of the verse before it's had a chance to begin.

The track's an odd one and seems to have been tossed off – it was the last track recorded on the day of recording, we know of no outtakes of it, and some of the singing at the beginning is slightly off-key, which is very unusual for someone as perfectionist as Elvis was at this point in his career. My guess, and it's only a guess, is that Elvis wasn't particularly keen on the song, which was brought in by Steve Sholes, and did it more or less as an obligation.

How's the World Treating You?

The final song written specifically for the sessions is a country ballad, co-written by Chet Atkins and Boudleaux Bryant. Atkins was of course one of the most influential country guitarists and producers around (and had worked on the sessions for Elvis' first album and "Heartbreak Hotel", while Boudleaux Bryant, usually in collaboration with his wife Felice, wrote a huge number of country and rockabilly hits, mostly for the Everly Brothers – songs like "Devoted to You", "All I Have to Do is Dream", "Wake Up Little Suzie", "Raining in My Heart", "Love Hurts", "Bye Bye Love", and dozens more that anyone who has listened to any white fifties rock and roll records at all will know intimately.

As you might imagine then this is one of the better originals written for Elvis at this time. It's not a particularly distinguished song -- there's nothing about it that jumps out as especially wonderful -- but it's a solid one, in the country ballad genre that Elvis actually seems to have been happiest recording in at this time. Elvis seems far, far, more comfortable on songs like this or "Old Shep" than he does on the Little Richard covers.

(Which is not to say that Elvis was in any way forced to do those records or anything like that. It seems apparent from everything that I've read that at this stage at least Elvis had near-complete control over his repertoire and record production, and if he recorded three Little Richard songs it was because he really liked Little Richard. But there's a difference for a performer between material one admires and material one can comfortably inhabit and embody, and for Elvis – who, let us remember, had only been performing at all for a little over two years when he recorded this album and whose released body of work was somewhere in the region of thirty tracks – he hadn't yet fully made that distinction.)

How Do You Think I Feel?

And the final track on the album is one of the more obscure covers on the record. Originally a 1954 single by Red Sovine, one which doesn't actually appear on Sovine's discography on Wikipedia, which starts with his 1955 country number one duet with Webb Pierce on George Jones' "Why Baby Why" even though Sovine's recording career went back to 1949, this is very different from the stuff that Sovine is now remembered for to the extent he's remembered at all – tracks like "Teddy Bear", a spoken-word recitation over country music about a "crippled boy" whose father had been a trucker, which makes "Old Shep" seem like a clear-eyed unsentimental tract on pure mathematical logic.

Sovine's original version of the song (which was written by Sovine's friend and mentor Pierce, along with Wayne Walker) is a bouncy, upbeat, country song – even though the lyrics are resentful ones about a broken relationship – with a vaguely exotica-influenced arrangement and some really nice fiddle and steel guitar parts. Elvis' version is an intelligent and fun cover version. It splits the difference between the kind of slavish cover version he did for the Little Richard tracks and the more radical reworking of something like "So Glad You're Mine". Scotty Moore's delightful guitar fills abut Elvis' shruggingly bemused vocal for a great album closer.

Elvis' first album-as-an-album is on average the better album than Elvis Presley. It's more consistent, more confident, and a more coherent statement. But while its lows are higher than the first album, the highs are lower – there's nothing here anything like as astonishing as that version of "Blue Moon".

Next time, we'll look at the first of what will turn out to be a lot of Elvis film soundtrack albums, as we look at his third album, the soundtrack to his second film (the first only had an EP, so we'll come to those songs as they turn up on compilations in future), Loving You, and I may also review the film as well.

Crisis Crossovers: All-Star Squadron.

I'm actually going to do things a little differently with the Crisis on Infinite Earths crossovers than I said last time. Rather than cover one comic per newsletter every newsletter, I'm sometimes going to cover multiple comics issues at a time, and not necessarily from the month that was forty years ago when the newsletter comes out (though the issue of Crisis I cover each month will be from that month).The reason for this change of plan is that when I did the first post I was in Portugal, and so I didn't have access to DC Universe Infinite, and didn't know which comics precisely they consider part of "the complete story" – if you go on that app (which I definitely recommend if you're a fan of DC superhero comics, as for a relatively small fee they have not quite every DC comic of the last ninety years but something surprisingly close to it) they have major storylines in separate sections. And in the case of Crisis on Infinite Earths they have two reading orders – they have just the twelve issues of the main series itself, and they have "the complete story" with many of the crossovers in story order. That's sixty comics in total, which is obviously not possible to do one-a-week between now and the end of December. So what I'm going to do is cover them in the order that they're in the app, so anyone who wants to can read along. So this week I'm going to look at All Star Squadron 50, 51, and 52, which all continue into each other, written by Roy and Dann Thomas. Next week we'll look at The Fury of Firestorm #41, the week after at Infinity Inc #18, and for the last week in February at Crisis on Infinite Earths #2.

The storyline in the order that it's portrayed in the DC Universe Infinite app has no crossovers between Crisis 10 and 11, and so when we get to that point I'll look at some other DC comics from 1985-86 that aren't part of the "official" crossover list but that tie in in some way, like possibly "Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?" We'll see when we get there, if I even continue this that long (though I hope to).

So, on to these three issues of All-Star Squadron, which are not in any sensible way of thinking good comics (certainly issue fifty is, I would say, an actively bad comic) but do work well as an opening for our look at the Crisis crossovers because Roy Thomas, specifically, is the perfect illustration of almost everything I talked about in the opening to the review of Crisis #1.

Roy Thomas was one of the first, if not the first (but as listeners to my podcasts know, repeat after me, "there is no first anything") comics fan turned comics writer/editor. He started out in superhero comics fandom before going to work for Marvel Comics as an assistant to Stan Lee, eventually taking over Lee's role as editor-in-chief when Lee in turn was promoted to publisher.

Thomas' time at Marvel was not fondly regarded by everyone in the comics industry – when Jack Kirby, Lee's erstwhile artistic collaborator, viciously satirised Lee as the TV evangelist Funky Flashman after he moved to DC, he gave Flashman a sidekick, Houseroy, who was the Smithers to Flashman's Mr. Burns. and this was largely the impression most people seem to have had of him.

But in truth, in Thomas' time at Marvel he actually created the basis of the modern superhero comics industry, for good and ill, because he made the "Marvel Universe" into a thing. Lee, Larry Leiber, Kirby, and Ditko created the "Marvel Universe" because a small group of people were all working on all the titles, and because it made financial sense to cross-promote a new or flagging comic with a guest appearance from a popular character. Roy Thomas was actually interested in the Marvel Universe as a coherent world that had to fit together and make sense. He had the attitude that fans (as in organised fandom, as opposed to just people who liked to read comics) did, and that became the attitude that Marvel editorial took during the seventies, and thus in turn what people expected from superhero comics more widely.

And when he moved over to DC in the late seventies, he took the same attitude to the DC multiverse, and especially to Earth-2. I said last time that for the most part you could read a DC comic and not have to care that there was a multiverse, and it would never come up. This is true about almost all of the titles DC was putting out, but not about All-Star Squadron and Infinity Inc, two titles that Thomas was writer/editor of (often co-writing with his wife Dann Thomas). These were set on Earth-2, unlike any comics written by people other than Thomas, and in the case of All-Star Squadron set in the 1940s. Not only that, but All-Star Squadron was an example of Thomas' desire to make everything into one big coherent story. Issues were literally set in between comics from the 1940s telling "missing" stories to explain points of continuity.

It's hard to convey just how bizarre a thing this was to do in the early 1980s. The comics "direct market" did exist by then – this is the method of distributing to specialist comic shops, rather than comics just being sold off magazine racks with every other publication – but until the late eighties the American comics industry was based on the assumption of comics being periodicals. They came out, they were on the racks for a month, and then the next issue came out. There would be very occasional reprints of old comics, but you simply couldn't make the assumption that your readers – who were mostly assumed to be around twelve, although it was of course known there was by this point a substantial contingent of adult fans – had easy access to even last month's issue of the comic they were reading, let alone one published forty years earlier.

(This kind of thing was happening a lot in what we might for want of a better term call "geek media" in the eighties. There's a Doctor Who story, Attack of the Cybermen, broadcast in 1985, which presumes that its audience are at least passingly familiar with the events of Tomb of the Cybermen, a serial that had been broadcast once, in 1967).

As you might imagine from this, Roy Thomas was not best pleased with the project of Crisis on Infinite Earths, which was to render all those 1940s comics no longer part of the continuity, and to get rid of the Earth-Two on which he set his stories, even if the reason for it was to create a coherent single "DC Universe" like the Marvel Universe he'd done so much to create.

However, to give Thomas full credit, despite his dislike of the basic idea, of all the DC creators he was the one who put the most effort into tying his comics into the story. Every DC title was given orders to connect with Crisis in some ways, but many of them were what gets referred to as "red skies" crossovers – the sky would be coloured red and maybe someone would comment on it to let us know that the Crisis was happening in the background, but otherwise they'd tell their own story as normal.

But Thomas' titles went all out, so we'll be seeing a lot of him in this series. And here we have three examples of that.

All-Star Squadron #50 is a bad comic, pure and simple. This is not the fault of any of the artistic team – pencillers Mike Clark and Arvell Jones, inkers Tony DeZuniga and Vince Colletta, colourist Carl Gafford or letterer David Cody Weiss. At worst the art is at a basic level of competence that doesn't draw attention to itself but just calmly gets the job done and tells the story perfectly clearly, and there are occasional pages where it does draw attention to itself in a good way. The hallucinatory sequence with the Spectre collapsing on page 5 does some nice, scratchy, wobbly-panel-border stuff that reminds me a little of Steve Bissette and John Totelben's work on Swamp Thing, and there's some nice post-Kirby Kosmic Krackle on pages ten and eleven, for example. Nothing groundbreaking, but at no point would you look at these pages and think "that looks like a bad comic".

The problem is with the script, by Thomas. As this is a fiftieth issue, the comic is longer than normal, at forty pages of story. In that story, I count forty-nine named characters, plus many unnamed characters interacting with them. Many of these named characters have multiple names – the bulk of them are superheroes with secret identities, and many of these secret identities also get mentioned.

In fact, everyone exposits information about themselves, which the other characters would presumably already know, to the people they're talking to at every opportunity, saying their name, their secret identities, and their relationships to the other characters, as well as catching the reader up on recent events in the comic. When you're doing this with a small number of characters, this kind of dialogue is clunky, but a useful convention of the genre. Even in Crisis, which has a far larger cast over the course of the story, it's handled relatively well because a bare minimum of the information you need to know to follow the story is conveyed.

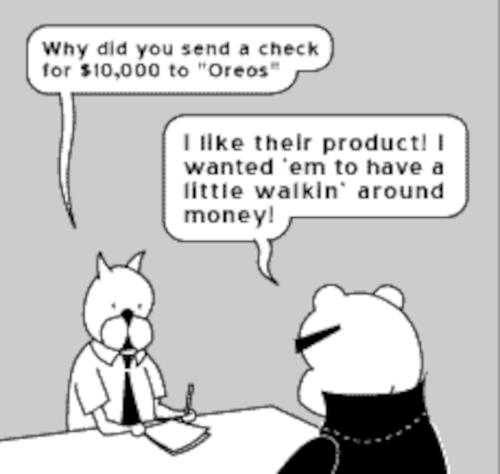

But, for example, we see someone in precisely four panels, in a wedding scene on one page. We are told – twice – that his name is Tubby (once just calling him Tubby, once Tubby Watts) and he calls himself "the rice-slingin' southpaw" in case it was unclear from the drawing of him throwing rice with his left hand what was going on and which hand he was using.

This is, essentially, every single line of dialogue in this thing. People are either stating their identities, talking about how they know the person they're talking to, telling us about things that happened in previous issues, or in some cases (because this is set in World War II) expositing about events in the war. It reads like someone has taken Wikipedia articles and copy-pasted them into the speech bubbles (obviously I know that Wikipedia wasn't a thing in 1985, before anyone brings that up), and you're just left thinking "that sounds like a more fun comic to read than this one".

It doesn't help that this is not actually a story, it's manoeuvring characters to be in position for future stories. The beginning is a light rewriting of a JSA comic from 1942, written by Gardner Fox, "Shanghaied into Space", in which Nazis kidnap the eight members of the JSA and put them in rockets and send them to the eight other planets of the solar system (this was when Pluto was still considered a planet). Here we discover that the rockets actually, thanks to the disruption caused by the Monitor sending Harbinger out to collect superheroes, sent the rockets through spacewarps to the versions of those planets in eight different universes. Then there's an expanded version of the brief scene from Crisis #1 where Harbinger picks up Firebrand and takes her to the Monitor's satellite, and various other characters end up going to other universes because of the effects of the Crisis. There's no plot, nothing gets resolved, and unless we already have some attachment to these characters we're given no reason to develop one. It's utterly insular and impenetrable, and just a bad piece of writing.

There's also some supposed humour with Plastic Man disguising himself as a privacy shield so he can watch a woman changing costume, which is treated as a lovable foible.

All-Star Squadron #51 though is actually quite an enjoyable comic. Dann Thomas is credited as co-plotter here (the pencils are by Clark for the first twenty-one pages and Jones for the last one, Colletta inks, and the team is otherwise the same), and that might be why this, unlike the last issue, actually has a plot. There is some of the expository name-saying dialogue, but this mostly takes place during an extended fight scene, rather than as in the previous issue with people standing around in various halls and chatting to each other, but the main point of the story is to explain the formation of the Monster Society of Evil, a supervillain team from the Captain Marvel comics of the forties led by a supergenius alien worm named Mr. Mind.

The Captain Marvel stories were always more lighthearted than other superhero stories, and so the Thomases have here given Mr. Mind a deliberately ridiculous supervillain origin story, a sort of precursor to Galaxy Quest. He is delighted by the broadcasts he picks up of Earth radio shows, and comes to Earth to meet his hero, the great comedian Charlie McCarthy. On discovering that McCarthy is actually a ventriloquist's doll and that Edgar Bergen did McCarthy's voice as well as his own, he goes berserk and forms a society of supervillains intent on destroying the world. It's fun, and charming, and utterly inconsequential, and that's absolutely fine,

And All-Star Squadron #52 is two stories, of sorts. The first half has the same team as issue 51, except that Alfredo Alcala is the inker. In this, three of our Earth-2 characters – Green Lantern, Johnny Quick, and Liberty Belle – have ended up on Earth-S, the universe where Captain Marvel lives. There's a brief fake-out confused fight (a standard genre trope when superheroes meet) before they realise that they're all on the same side and should actually be fighting the Shadow Demons that are attacking them. After the fight, there's a little side-quest when Green Lantern's ring runs out of power and he has to go and find the meteorite that the lamp it's charged from in his reality was made of, and then they all go to Captain Marvel's mentor, the wizard Shazam, who sends them back to their own reality.

It's competently executed enough, but while it does have a plot (so again beating issue fifty quite handily) it has no thematic resonance, so no stakes. Our heroes have to fight some baddies, and then collect a token, and then go home. The end. It's not a story that needs to exist.

The second half is "Shanghaied into Hyperspace: Interlude One", and we will presumably see another seven interludes in future issues. The way the 1940s Justice Society comics would work was that they would start with the team all getting together and facing some problem, then they would be split up and each member would have their own mini-adventure, before all getting back together at the end.

Here we have Hawkman's adventure from 1942's All-Star Comics #13, originally written by Gardner Fox and Sheldon Moldoff and drawn by Joe Kubert. The art credit here is "Art by Al Dellinges, utilizing the golden-age art of Joe Kubert". I thought from that credit that this was a case of Dellinges basically just redrawing Kubert's work exactly, because it has some of the inept anatomy and stiffness that characterises some of the early days of superhero comics, but it's actually closer to "in the style of" than a copy – All-Star Comics #13 can also be read on DC Universe Infinite – and Kubert's work even back then is much better than Dellinges' here.

Dellinges is not a widely-known comic artist, but he seems to have been primarily know as (as I've seen him described) "a human Xerox machine", particularly of Kubert's work – he redrew exact copies of Kubert's line-art for fan publications which wanted to present black and white versions of Kubert's drawings which were published in colour on cheap paper and for which the original art was lost. Here Roy Thomas (I assume only him because there's no new plot here, and Dann Thomas is credited only for plotting) has expanded the original story, showing events in several panels that were covered in captions in the original, and adding in overly-verbose dialogue, and so Dellinges has had to draw an entirely new comic, but one in which reproductions of many of Kubert's old panels would fit seamlessly, to preserve Thomas' conceit that what he is doing is telling a fuller version of a story we've already seen.

The plot, in both versions, is the same, and is sub-John Carter/Flash Gordon pulp hokum – Hawkman, put in a rocket by evil Nazi scientists, lands on Saturn (the Saturn of another dimension here, unbeknownst to, but suspected by, Hawkman) and immediately saves the life of someone being attacked by evil bird-monsters. The man he saved tells him that the part of Saturn he is in now is a democracy, but there's an evil tyrant nearby ruling with an iron fist just like Hitler is on Earth – and worse, the rescued victim is in love with the tyrant's daughter, but the tyrant is keeping her locked up so she can't marry him. Obviously Hawkman immediately flies off, rescues the princess, and deposes the tyrant, and is then given a reward of a case full of radium, which is "as plentiful as water" on Saturn.

This is fine as cheerful nonsense meant for very small children, as the original comic was, but there's something faintly absurd about trying to treat this story as some kind of sacred text which needs to be retold and elaborated on and made in some way serious. It reminds me, in a way, of the current fad for things like deeply reverential, elegaic, sequels to Ghostbusters aimed at people who watched that film forty years ago when they were small and took it seriously, and don't yet realise that it was a comedy film. (It also, of course, reminds me of the work of Geoff Johns, the comic writer who is very much the modern-day Roy Thomas).

I said last time that Crisis on Infinite Earths didn't need to happen, and I still think that, but in these comics Roy Thomas makes the best possible case that it was essential. If this was all the DC Multiverse had to offer, it would have deserved to burn.

Next time – Firestorm. See you in a week.