Writing Ethics, "Loving You", and Fury of Firestorm #41

The Ramble

Before I begin, I know this newsletter is not currently on quite a weekly schedule, and this is coming out at the end of the calendar week, rather than precisely a week after the last episode. I have been suffering recently from autistic burnout, a thing that happens to all autistic people at times, and I've been trying to balance getting work done at something like a reasonable pace and not pushing myself so much that I can't function any more. Since the last newsletter I've written a detailed proposal for the collaborative project I hinted at last time, and most of the script for a Patreon bonus on the Box Tops which I hope I'll be recording tomorrow, as well as making some final structural decisions about the next main episode I'm in the process of writing, which is what I want to talk about here.

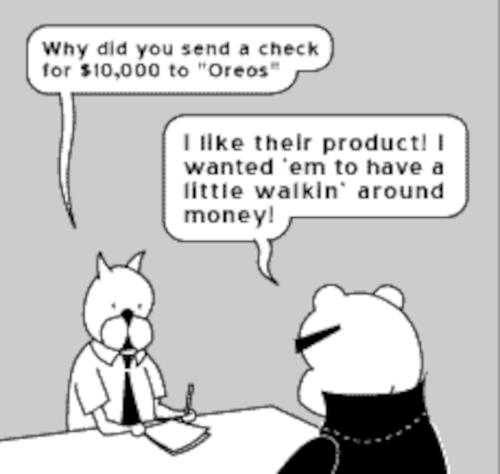

One thing I've been thinking a lot about recently is the relationship between art, craft, honesty, and manipulation, and the ethics of being an artist (and I do consider my podcasts to be art, pretentious though that may be).

When I started my podcast back in 2018 I was a competent writer and storyteller, but I like to think I've become much better at it in the ensuing years. I've also had to become much better at it because of the way the nature of the work has changed, as I've had to deal with a much greater mass of material.

When I started out and was doing an episode on, say, Gene and Eunice, I could make the episode concentrate on precisely what I wanted it to, and say just what I wanted to say, because a) I had almost no audience, so no demands, b) there was very little information out there about Gene and Eunice so I couldn't say much even if I wanted to, and c) I could assume that the audience I did have would either be totally unaware of Gene and Eunice's work or would just be happy to see them recognised at all. The episode then becomes "this is who these people are, this is why they're interesting and why their story is important, here's a couple of clips of their best music, see you next time".

But in the years since 2018, two things have happened. The first is that my audience has increased by orders of magnitude, and the second is that I'm now covering artists like the Beatles and the Beach Boys and the Rolling Stones, who whether you think it's deserved or not have a much greater cultural presence still than Gene and Eunice or Vince Taylor or even Elvis, and who also have far more information available about them than those artists.

This means I have to write episodes that work for multiple incompatible audiences. When doing an episode on, say, the Beatles, I have to take into account the people listening who actually know more about the Beatles than I do; the people who think they know a lot about the Beatles but have actually taken in a lot of misinformation; the people who are aware of the Beatles' existence but don't see what all the fuss was about; and given that I'm trying to write a history that will actually work as a history and hopefully be referred to in future, I have to also assume that at least some of my listeners will, either now or in the future, not know anything about the Beatles at all.

This is not as bizarre an assumption as you may think. Elvis, for example, was someone who dominated pop culture awareness even decades after his death and who was having posthumous UK number ones as late as 2005 – Elvis' last number one to date, in fact, was replaced on the charts twenty years ago today as I write this (a few days ago as I post). But extremely quickly after that, he almost completely vanished from awareness in the larger culture as a demographic cliff hit the generation who had found his music revolutionary, and until Elvis Presley Enterprises started a hugely successful multi-pronged publicity campaign culminating in the Luhrmann film a couple of years ago I would have bet that the average person under thirty would not be able to name an Elvis song, and he had about as much cultural relevance as Glenn Miller.

The Beatles may, long-term, be as continually relevant as Shakespeare, or they may be closer to Kay Kyser and his Kollege of Musical Knowledge (the single most popular band in the US in the late thirties and early forties), and I want my work to be accessible whichever is the case.

So this means that in a Beatles episode I have to still do the things I did in my early episodes – "this is who these people are, here is why they are important, here's the interesting thing I want to tell you about this episode, here's some clips of their best music, see you next time" – but I also have to:

Include all the things that get included in the popular histories of the group, because I want to tell a somewhat comprehensive story

Include something that makes it worth sitting through for the people who already know more than I do about the Beatles – some fact or angle that they don't know or haven't thought of, even if it's not the thing I wanted to say.

Correct misinformation believed by people who formed their opinions by reading Rolling Stone in 1968 and haven't seen any reason to update their views (seriously, Rolling Stone is the bane of my life).

And explain to people who have never encountered the Rolling Stone-based misinformation in the first place what that misinformation is and why I'm bothering to correct a lie they've never encountered.

These aims are often mutually contradictory, and so require me to do a lot more work in terms of structuring the episodes in order to provide a coherent throughline through what would otherwise be an incoherent mass of facts and digressions. Often this means putting in even more facts and digressions in order to connect these disparate threads together.

Doing that means that I have to pay far more attention to the craft side of the writing than I had to at the beginning. I have to make sure, for example, that the ending of an episode is relatively powerful, because it's one thing to ask someone to sit through twenty-five minutes of a quite interesting story and then say "well, that's it, see you next time", it's quite another for them to get through two to four hours without a big payoff.

And one of the few bits of writing advice that I've found very useful over the years is that the most important part of a story is what is known as the validation. This is something that comes after the main plot of the story is over, and which tells people "this has ended, and this is how you feel about it".

It's called the validation because in the classic form, particularly in drama, it serves the purpose of reinforcing "the thing you saw really happened". The most archetypal way to do this is to have a secondary character briefly comment on what has happened, summing everything up – a secondary character because in a narrative they're taking the viewpoint of the audience and so confirming for the audience that what they saw affected people other than the main characters. Think of Horatio and Fortinbras' conversation at the end of Hamlet. Or Marlene Dietrich in A Touch of Evil saying "He was some kind of a man. What does it matter what you say about people?", or the end of King Kong – "No, 'twas beauty killed the beast".

More broadly, in other forms of narrative, it's just something that can be as little as a few sentences, but something that clearly says "this story is over now, and here's how you should feel about it." Think of, for example, the ending of 1984 – "He loved Big Brother."

And I have, I think, got very good at coming up with that kind of ending – people often single these out as being particularly impressive, and talk about particular endings having made them cry. And this simultaneously makes me feel good, but also feels weird, because it feels on some level rather crass and manipulative to be making people have a particular emotional response because of a conscious craft choice I've made. Even if, as it often is, that emotional response is also the one the material has made me have while writing. Making people feel things by accident feels honest in a way that making a deliberate decision doesn't, even though in many ways making a deliberate decision is more honest, because it's successful communication.

I'm thinking about this a lot when it comes to the episode I'm working on because there is a thing I'm planning on doing – not at the ending this time but elsewhere in the narrative – which I think will be especially powerful, but which might also be a little tasteless. It's a formal trick in the writing that will tie several of the threads I've been playing with in these episodes together, thematically at least, and which if I do it right will hit like a gut punch. I explained this in a group chat I'm in and got the response "Um, yeah, bit of eww, bit of cool" from one of my friends, which about sums it up.

But this is the problem of course. I have to remember that I am writing about real people, and that in the case of these episodes, and this episode in particular, I'm talking about the Manson murders, a series of murders of real human beings, many of whom have loved ones still alive, and that "cool" should not be something anyone thinks about any aspect of that. By trying these writing tricks in a situation like this, am I conveying the horror of what actually happened with appropriate respect, or am I being overly sensationalistic – or am I just revelling in my own cleverness and the fact that I can do things like this?

I suspect the answer is "yes", and that I'm doing all those things.

Anyway, this episode, when it's done (which won't be for at least another week or two), will either work really well or be in profoundly bad taste. All I can say is that I am very aware of the pitfalls and not wanting to do anything too awful. And that I am profoundly looking forward to being out of this period of 1968/69 where I'm having to deal with back-to-back horror stories.

Link of the Week

This is annoying. I had planned to put in two links today, because several film studios have been quietly releasing full older films onto YouTube, on their official channels, to watch for free without advertising, so I was going to link to the playlist that Warner Bros had put together at https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL7Eup7JXScZyvRftA2Q5hv69XiegDm6tQ of free full films, including True Stories (the David Byrne film), Waiting For Guffman, and several others that are definitely worth watching, and to the similar playlist of classic horror films from Sony at https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLi-CMBfEQuDjV6JvrRlroVTLCJFob3Ne2 .

Unfortunately while those playlists were both up a few days ago, at least in the UK where I am every video in the Warner Bros playlist is now showing as unavailable, as are half the films in the Sony playlist – presumably the publicity these playlists got from the article I found them in was enough to get some executive to reverse course on the decision to make these available. I've left the links here though in case they work for people in other countries still – it may just be some regions.

Anyway, this is why I still buy physical media, or at the very least DRM-free downloads. Warners can change their mind about making Waiting For Guffman available on YouTube whenever they feel like, but they can't (yet) take my DVD copy off my shelf.

Elvis Album of the Week: Loving You (1957)

Very soon after Elvis became a star, Colonel Parker decided that he should start appearing in films, on the basis that this was the most efficient way to make money from Elvis' appearances. If he did concerts, he could only appear in front of a few thousand people at a time. If he did TV, then millions of people could see him but they wouldn't be paying. But the cinema? That was a way to get millions of paying customers from a single performance.

And initially this was something that Presley was very enthusiastic about, especially as he was initially told that he would be performing in proper films, not just in quickie rock and roll exploitation films. He particularly loved the work of James Dean and Marlon Brando, and he had enough natural acting talent that he could quite easily have replicated the career of Frank Sinatra, the nearest person to him in terms of career previously. Sinatra, like Presley, had been a revolutionary vocalist with a fanbase of mostly teenage girls, but in his case he had transitioned to becoming a hugely respected actor in films where he didn't sing at all.

Elvis' first film, Love Me Tender, had seemed initially to be intended to position him in the same way. When he had first been cast, in what was a by-the-numbers Western, it wasn't even a singing role, and not a major part, but soon an excuse was found to have his character perform a handful of songs in the film. (There were only four of these, not enough for a soundtrack album, so we'll be encountering those songs as they turn up on compilations). The film was also promoted with Elvis as the star, despite him having a fairly minor role.

But when it came to his second film, Loving You, we see the beginnings of the Elvis Film as it gets talked about. Or rather, we see the start of phase one of the Elvis Film. Elvis' films actually came in multiple phases, and there were periods of greater or lesser artistic quality as time went on, and I will be watching several of them as we get to their soundtrack albums (not all, by any means, but several of them.)

The first phase of his films, before he was drafted in 1958, consists of films which to a greater or lesser extent have him playing "himself" in fictionalised versions of his own story. In the case of Loving You he plays Deke Rivers, a young singer who starts out as the featured vocalist in a country band led by an older former star, Tex Warner. The band is managed by Warner's ex-wife Glenda, who he's still in love with and who has a knack for publicity stunts, but who is in love with Deke, and features a female singer, Susie, who Deke in turn is in love with.

Given this information, you could probably write the entire script yourself, especially if you're at all familiar with the pattern of the mid-fifties teen rock and roll exploitation film – the old fuddie duddies in power want to stop this evil rock and roll music but there are impassioned speeches by Glenda and by Deke's young fans, pointing out that back in their day people said exactly the same things about jazz, and aren't the kids just having harmless fun? Eventually Tex and Glenda pair off, as do Deke and Susie, Deke becomes a major star, and everyone is happy.

It's slight stuff, and it does Presley no favours as an actor – in these early films his star persona is set to "brooding", and in a film like this where the major dramatic interest is which of two extremely beautiful women in love with him he ends up with, and how that will impact the extremely successful singing career that was manufactured for him with no real effort on his part, that comes off as "sulky teenager". In his next couple of films, with some actual drama added, that works far better.

But that's not to say that Loving You is a bad film of its type. It's not well served by its current DVD release – a barebones release, and not only that, one which has a pan-and-scanned Academy ratio version of the film even though it clearly says at the start that it's filmed in Vistavision (a real shame, as this is the only one of these early Elvis films to be shot in colour) – but it's a perfectly competent example of the type.

And it's clear that Elvis was trying in little ways as well as big ones. One thing I found notable watching the film was that when he's miming to songs, he plays the rhythm guitar part properly, including a few small passing chords. It's not a big thing, and not a thing any non-musicians or even most actual musicians would care about, but it makes a difference.

Loving You also provided what ended up being the first of a lot of soundtrack albums released by Elvis over the next few years. Not every film he made had enough songs to make up a soundtrack album – and as a result we'll also look at a few CDs that contain compilations of multiple soundtrack EPs as this collection goes on, as well as finding odd tracks from films on non-soundtrack albums and compilations – but in the twelve years from 1957 he released six studio albums (two gospel albums, a Christmas album, and three normal pop albums) and seventeen film soundtracks plus one TV show soundtrack.

Unlike some of them, this isn't a "pure" soundtrack album. Side one contains all the songs used in the film, though sometimes the performances used in the film were different from those used on the album, while side two is made up of other recordings made at the same time.

While up to this point, Elvis' albums had been recorded at RCA's studios in Nashville and New York, or in Sam Phillips' Sun studios in Memphis, this was recorded at two studios in Hollywood mostly used for film soundtracks, and the recording sessions by all accounts did not run smoothly. While previously Elvis and his band had managed to knock out multiple tracks in short order, for these sessions they would often not complete a single song in a day. In part that was because some songs needed multiple versions (different partial takes for different scenes in the film, plus a full version for the album) but also in part it was because the early sessions took place in Paramount's studios, which were apparently not at all conducive to recording, before they switched to the more congenial Radio Recorders.

It may also be because Elvis didn't have as much control over the material as on his previous albums – while he was under a contractual obligation to perform a certain number of songs published by Hill and Range Music, he'd still generally had free rein within that limitation to pick the material he wanted to. Here, though, the songs had to fit the film they were being recorded for.

And possibly because of the different atmosphere in the studio, possibly because of differences in acoustics, or possibly even just because Elvis was getting more professional, this has a much slicker, poppier sound to the actual recordings, even though the musicians on the record are largely the same – Elvis, Scotty, Bill, and DJ all playing their instruments, the Jordanaires on backing vocals, and two of the Jordanaires adding keyboards.

There's also additional acoustic rhythm guitar from session player Tiny Timbrell on a handful of songs, and for the first time we have piano from session pianist Dudley Brooks, the session player at Radio Recorders in Hollywood who would play on over a dozen Elvis albums (and who is also the first Black performer we have seen turn up on an Elvis record, for those of you keeping track of Elvis and race).

But in general it's largely the same people we've seen on the previous Elvis albums, so it's quite surprising that it sounds slicker and poppier than previously. Partly, though, this may be down to the songwriting. Here for the first time we have an album where almost every song was written specifically for Elvis by professional songwriters, with only four of the twelve tracks (all on side two) being cover versions, and so we have the attempts of Brill Building hitmakers to write things that they think sound like the R&B and country songs that Elvis had previously been covering.

Of course, in the case of Leiber and Stoller, who provided the title track, they had got their start by writing that kind of material, but some of the other writers aren't quite as au fait with the genre, and it shows – and even in the case of those who do understand the assignment, the fact that these songs have been written for Elvis-the-teen-idol means that we get no more songs about avoiding the landlord because you can't afford the rent, or about clandestine hookups with trans sex workers.

1956 had been the year that rock and roll had thoroughly burst onto the mainstream of American culture – 1957 was the year that the mainstream started to fight back, to sand the rough edges off it, to take this music that had been made by Black, queer, disabled, or at the very least impoverished people, marginalised music that had hit the mainstream and was now appealing to white suburban teenagers, and make it into... well, into white suburban teenage music. Music that was free from the idiosyncracies that made the first generation of rock and roll music so appealing.

Some of that white teenage pop music was very, very good, but it's not the same as the earlier material, and the Loving You soundtrack is definitely a transitional album for Elvis. He would not make another normal studio album for three years, until after his time in the Army – between now and then we have a Christmas album and several compilations to get through – and when he did he was a very different artist. But here we have an awkward transition between the Hillbilly Cat and the later artist. These are, for the most part, thoroughly adolescent songs, and as a collection of songs this is the least interesting we've seen from Elvis so far.

Mean Woman Blues

We start with an exception to that rule. For literally decades I was under the illusion that this was a cover version, rather than a song written specifically for Elvis, because almost as soon as he released it it got picked up by other rockabilly artists like Jerry Lee Lewis and Roy Orbison, and so I assumed it was an old blues record they'd all picked up on.

But no, this was written for Elvis by a jobbing songwriter. But unlike many of the other writers working on this album, Claude Demetrius had a real background in R&B. He'd written "I Was the One", the B-side to "Heartbreak Hotel", but before writing for Elvis his biggest hits had been for Louis Jordan, for whom he'd co-written "Mop! Mop!", "I Like Them Fat Like That" and "Ain't That Just Like a Woman" among others. He'd also written for Louis Armstrong, and he also wrote a song for the Blenders, which saw legitimate release as "Don't Play Around With Love", but became much more popular in its bootlegged uncensored version as "Don't Fuck Around With Love" (those of you who haven't heard that one can find it at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7jGvwFs5MLU . It's a hoot.)

In short, there's a reason that "Mean Woman Blues" got picked up by everyone – it's a generic twelve-bar blues, but a fun one, with a wit and a mastery of the idiom that you'd not often see from assembly-line rock and roll. And Elvis and the band make the most of this, turning in an enthusiastic, powerful, performance. Easily the best thing on the album.

(Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear

This, on the other hand, is asinine. Kal Mann and Bernie Lowe, who wrote it, went on to be the masterminds behind the careers of Chubby Checker, Bobby Rydell, and the rest of the Cameo-Parkway stable of artists, and this is a good example of the kind of material those artists would later specialise in. There's nothing wrong with cynical manufactured pop – I'm a Monkees fan! – but there is something wrong with bad cynical manufactured pop. Elvis and the musicians make the best of it and almost turn the sow's ear into something approaching a silk purse – and it certainly was a success commercially, going to number one on the pop, R&B, and country charts – but the song might as well be called "Will This Do?"

Loving You

This ballad is the first song that Leiber and Stoller wrote specifically for Elvis. It's clearly not a song they thought of particularly highly – in their autobiography it rates the single sentence "Then there was “Loving You,” a ballad we wrote that became the title song of his next film" – but second-tier Leiber and Stoller is better than most people's best. The lyrics aren't Leiber's best by any means – there's none of the wit of his contemporaneous work for the Coasters, and it seems he hadn't yet got a handle on how to write for Elvis' persona, as the two hadn't yet met, so it's very much a by-the-numbers love lyric. But Stoller's melody is exceptional, and Elvis gives a great performance with a very stripped down backing.

Got a Lot of Livin' to Do

Written by Aaron Schroeder and Ben Weisman, this is an example of Elvis and the band elevating poor material. The song is a piece of frothy nothing, but it's performed with enough conviction that it comes out as a fairly convincing rock and roll track. There's little to say about this one, but it sits on the positive side of neutral.

(One point of interest – while he mumbles the line, I'm sure that sometimes Elvis sings "no-one who I'd rather do it with" but other times "whom I'd rather do it with", which seems to say something about the kind of writers Schroeder and Weisman were).

Lonesome Cowboy

Heard in the context of Elvis' development as a performer, without knowing some of the horrors to come, this is bizarre.

To be clear, this is neither a particularly bad song nor a bad performance, but it's a song unlike anything that Elvis had recorded before, and unlike anything in today's popular music, in a style which was already going out of fashion when it was recorded.

Sid Tepper and Roy Bennett, the team who wrote it, wrote a huge number of songs for Elvis' films, and would also write for Cliff Richard (notably "The Young Ones") but their big pre-rock hits had been things like "Red Roses For a Blue Lady" for Guy Lombardo and his Royal Canadians, "Suzy Snowflake" for Rosemary Clooney, and "The Naughty Lady of Shady Lane" for Dean Martin.

What they turn in here is a Western cowboy ballad that could have been recorded in the 1940s by Gene Autry or Roy Rogers, and would have fit perfectly well into one of their singing cowboy films, but which does not fit, at all, with anything else on the record. However, it's not a bad example of that kind of writing, and Elvis makes it interesting by showing a side of his vocal style we've not seen much before. While the instrumental and backing vocal arrangement is pretty much by-the-numbers for this kind of record, with its clip-clop percussion and "Tumbling Tumbleweeds" bass, here Elvis chooses to take the song at points as if it's almost an operatic piece rather than a cowboy ballad, splitting the difference between two of his big but less commented-on vocal influences, Mario Lanza and Dean Martin, giving an overblown, overpowering performance whose theatrical excess of emotion has more than a little camp about it.

It's an odd track, and I'm not sure if it's a good one, but it's definitely an interesting one in this context as what seems like a one-off. But as we'll see later it's very far from being that.

Hot Dog

"Hot Dog" is the second Leiber and Stoller song on the album, and one of their less impressive. In fact it's barely a song at all – three of the songs on side one of this album come in at under two minutes, and this one comes in at 1:13. It's barely started before it's over, and it's Leiber and Stoller writing pop froth to order, and it's given a train feeling mainly so it can illustrate a travel montage in the film. But DJ Fontana does a great job with the vaguely Latin feel of the drums, and Elvis' vocal is playful and fun. Not a record I ever think about or choose to put on, but not one I'm ever unhappy to hear either.

Party

Later and more famously covered by Wanda Jackson as "Let's Have a Party", this is, along with "Mean Woman Blues", the standout song from side one, and it comes from a writer with a very similar background. Jessie Mae Robinson, who wrote this, had a long career writing for people like Dinah Washington, Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson, Louis Jordan and Charles Brown before her song "I Went to Your Wedding" (which I discussed in the "Earth Angel" episode of my podcast, as that song ripped off a chunk of it) crossed over to white performers and audiences after Patti Page covered it. She also later wrote "The Other Woman", the gorgeous Nina Simone song.

So "Party" is, like "Mean Woman Blues", someone writing an attempt at a generic rock and roll song but from a position of thoroughly understanding the genres from which rock and roll had so recently sprung, and so it's a light, fun, song, but with cultural specifics that simply aren't there in the work of the songwriters coming from straight pop. Schroeder and Weismann, Tepper and Bennett, Mann and Lowe might all have written a song about having a party, but none of them would have included the line "everybody come and taste the possum Papa shot".

The kind of party where the food served is possum shot by one of the attendees is a very different party from a teenage party at the soda fountain, and from an elegant cocktail party in Manhattan. Many of the new songwriters who were bringing songs to Elvis had experience of Manhattan and were writing about soda fountains, but Elvis had come from that other world – when he had bought Graceland as his family's mansion, his parents had brought livestock along.

So here we have something that properly fits Elvis' idiom, while still fitting the brief of being a frothy pop party song. And Elvis and the band rise to the challenge. It's another short one, not quite reaching a minute and a half, but side one is definitely structured to start and end on its best tracks,

Blueberry Hill

Side two, unlike side one, is made up of tracks not included in the film (though one was intended for it) and so it's got several cover versions on it, starting with the opening track. "Blueberry Hill", written by Vincent Rose, Larry Stock, and Al Lewis, was an old standard by this point, having been written seventeen years earlier and becoming a hit in the early forties for Glenn Miller, Gene Autry, and others. But this version is very obviously modelled after Fats Domino's version from the previous year.

Halfway between a parody and an homage, the backing track is a fairly close approximation of Domino's rhythm section, with the standard Dave Bartholomew bassline and Brooks doing a fairly decent attempt at Domino's New Orleans piano style. Presley here is affectionately mimicking Domino's New Orleans accent, and it's the kind of thing that one could easily see as being problematic appropriation or even close to minstrelsy, but to my ears it's very clearly affectionate and admiring, and Elvis was always extremely vocal about his admiration for Domino. Your mileage may vary, of course, but I think this is a fun track, and kicks off a shorter second side which I also think is a much stronger side, because it's Elvis choosing songs to sing that took his fancy rather than songs which had to be fit to a film.

True Love

Another version of a then-recent hit from an older generation of songwriters, this Cole Porter song had originally been recorded the year before by Bing Crosby and Grace Kelly for the film High Society (which incidentally is one of the great film musicals of all time, and one I'd highly recommend to anyone who hasn't seen it – and I say that as someone who is not generally a fan of musicals).

Here it's used as a chance for Elvis to finally get to do what he always secretly and not-so-secretly wanted to do, which is to be not a solo singer but a member of a gospel quartet. After the intro, for all the verses Elvis is singing in block harmony with the Jordanaires, just one voice in the middle of the stack, though a little bit higher in the mix than them, with the voices backed just by a plucked guitar (and what might be Black doubling the bottom notes on his double bass, but if so he's almost inaudible).

On the middle eight we have what I think might be the first example of an overdub on an Elvis record – and certainly the first one we've encountered going through album by album – if it is an overdub. Normally at this point Elvis' tracks were cut as live in mono, but for the middle eight either Elvis is double-tracking himself in harmony or one of the Jordanaires is doing a really good imitation of his voice in very close harmony. I keep going back and forth about which I'm hearing and convincing myself it's one, then the other, and I'm sure within five minutes of me posting this someone will say "How could you possibly think that was a double-tracked Elvis? It sounds nothing like him!"

But Elvis got his start harmony singing, and he would often find people who could double him quite spookily to sing with – I always find it amazing how closely he and Charlie Hodge could match each other at times, for example, and here the two voices sound very close together indeed.

It's a track that has absolutely nothing to do with rock and roll music – it's a song for a crooner, by a Tin Pan Alley veteran, reinterpreted for a Southern (white) Gospel quartet – but it's a very, very, lovely interpretation of the song, and strongly better, to my ears at least, than some of the rock and roll that makes up the first side of the album.

Don't Leave Me Now

Written by Schroeder and Weissman, I believe intended for inclusion in the film, Elvis was dissatisfied with the performance on this one, and while it was released on the album, he rerecorded it in a new version for the soundtrack of his next film, Jailhouse Rock.

(Because Jailhouse Rock didn't get a soundtrack album, just an EP, and that EP isn't compiled into one of the discs that make up the fifty-CD set I'm working through, we won't be dealing with that version in the course of these reviews – though when I finally get through them all, if people aren't completely sick of me talking about Elvis, I might do a mop-up post looking at the non-album tracks released during his lifetime which aren't on that set).

A slow, plodding, piano ballad with a similar feel to "Blueberry Hill" – in fact it wouldn't surprise me if it was written as a knock-off of that song after Domino's hit, though the resemblance is only a vague one, and it's certainly not a straight lift – this suffers in comparison with that track. It's not a bad track, but it's easy to see why Elvis wanted another crack at it when it was used for Jailhouse Rock, rather than just using the version he'd already done.

Have I Told You Lately That I Love You

Not the Van Morrison song (which is actually just called "Have I Told You Lately"), this is a country-pop song written by Scotty Wiseman for his duo Lulu Belle and Scotty in 1944, and as well as being recorded by them had also been a hit for both Gene Autry and Bing Crosby with the Andrews Sisters. Elvis' version is pretty much in the mainstream of versions of the song, with the main difference being that he doesn't have the strings of the Crosby/Andrews version nor the fiddle of the Autry, but it's a nice midtempo country shuffle, with percussion provided by Elvis slapping the top of his guitar.

Elvis goes through a few different vocal styles in the course of this track, and it's interesting to see how much more assured he is in his singing here compared to the previous album. While there he seemed to be experimenting, trying a lower vocal range to see what it would do, here he moves smoothly and almost imperceptibly between a Dean Martin style croon and an exaggerated self-parodic hiccup.

A minor track, as many of these tracks are, but a pleasant one. Which could really sum up this album as a whole – there's very little here that's at all essential, but there's also very little here I wouldn't always be happy to hear. The highs aren't all that high, but the lows aren't low at all.

I Need You So

As with side one, side two is bookended by its two best tracks. While side one started and ended with uptempo rock tracks, here we start and end with mid-tempo R&B piano ballads. "I Need You So" was originally recorded by its writer, Ivory Joe Hunter, in 1950. For those not familiar with his work, Hunter was one of those singers like Nat "King" Cole and Charles Brown who threaded the needle between R&B and slicker crooning – Hunter, like Brown, had been a member at one point of Johnny Moore's Three Blazers.

Hunter was a favourite of Elvis', and had recently visited him at Graceland, where the two spent a day together singing some of Hunter's songs. Like the other cover versions on the album, this is a fairly faithful cover of the song, with the Jordanaires' backing vocals taking the place of the orchestration on the original. It's quite astonishing the sheer variety of vocal styles Elvis goes through in this performance, though, compared to Hunter's smooth original.

Some of it feels a little mannered – there's a bit of an over reliance on the hiccupping "uh-I-uh-need" vocal tic, for example. But he's jumping around registers all over the place here – both vocal, going from a deep, resonant, chest voice to a much higher head voice, even going into his nose at points – and emotional, moving in the space of a few syllables from a knowing, winking, self-consciousness to a cracked, utterly sincere, plea.

It's the kind of thing that shouldn't really work – in the hands of a less skilled singer it would be a horrible mess – but as it is it shows just how sophisticated a singer Elvis already was, aged just twenty-two. There's a conscious artistry here which doesn't get in the way of the communication of actual passion (which in its way answers the questions I posed myself in the ramble part of this newsletter, doesn't it? Assuming I have the same mastery of my medium aged forty-six that Elvis did aged twenty-two, which is probably not a safe assumption...).

Loving You is, in truth, not an album about which there is a great deal to say – we'll hit more of these as I go on with this project.

Crisis Crossovers: The Fury of Firestorm #41

And here we hit a comic about which there is not a great deal to say either. Like Loving You, this is a perfectly enjoyable, well-executed, example of the kind of thing it's trying to be, but the thing it's trying to be is not something with a great deal of depth to it, and does not admit of much analysis.

This issue is mostly interesting for allowing us to talk more about something that was a focus of the first in this series of essays – the anxiety of influence DC had about Marvel at this time. In the sixties, Marvel Comics had largely reinvented superhero comics, and one of the ways it had done that was by bringing in teenage superhero characters, who (naturally, as teenagers) felt rather more angst than the more mature characters DC had specialised in up to this point. Characters like the flame-bodied, rebellious, Human Torch of the Fantastic Four; Spider-Man, whose plots had as much high-school soap opera as they had supervillain battles; and the X-Men felt fresh and new when Kirby, Ditko, and Lee created them before rapidly becoming tropes themselves.

Writer Gerry Conway, who co-created Firestorm with Al Milgrom, and who writes this issue (pencilled by Rafael Kayanan, inked by two inkers credited as Akin and Garvey, lettered by Duncan Andrews and coloured by Nansi Hoolahan) had, like the other writers we've seen thus far, started out in comics fandom before going on to work for Marvel, and he had written for both Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four. So when he moved over to DC, he wanted to create a character who had some similarities to both the Human Torch and Spider-Man, while being distinct from either.

So in Firestorm The Nuclear Man we have a character who has similar high school soap-operatic plots to Spider-Man's, but where Peter Parker is a nerd, Ronnie Raymond is a jock. Like the Human Torch, Firestorm can fly and has a flame motif, though his flame is only in his hair, not his whole body. And, like every classic era Marvel character, Firestorm got his powers from an accident involving radiation. Firestorm is, though, vastly and ludicrously more powerful than any Marvel character, being able to manipulate matter to such a degree that he can transmute elements – here he turns some falling masonry that's about to kill some students into harmless balloons and party poppers.

The other big twist in the character, along with him being a jock rather than a nerd, is that Firestorm has two secret identities. The accident merged two people – high school jock Ronnie Raymond and Nobel Prize winning physicist Martin Stein – and they can separate and live independently in their normal identities, or they can merge themselves together into Firestorm, with Raymond in control but Stein as a disembodied voice guiding him.

Even this, though, is a literalising of a very Marvel metaphor – much of the angst in other early-sixties Marvel characters, like the Hulk, was around there being two distinct sides to their personality, neither of which can control the other. Stein and Raymond in this regard are just a slightly more literal take on this classic superheroic duality.

In short, Firestorm is an "I can't believe it's not Marvel" character, and this is an "I can't believe it's not Spider-Man" comic. It's also the first Firestorm comic (as opposed to comics where he's a member of a team like the Justice League) I've ever read (apart from a few issues of Dwayne McDuffie's run on the title in 2007, by which point Firestorm was a totally different character) and the fact that I could absolutely follow it is, on the positive side, testimony to Conway's ability to write clearly for people for whom it's their first issue, and on the negative side is an example of how it's following the beats of stories any superhero comics reader has encountered innumerable times.

The basic plotline is one that has happened to every teenage solo protagonist of a superhero comic – our hero has grown up enough to go off to university, where some of his supporting cast from high school have also travelled, along with some new archetypes for him to meet (here there's a much bigger jock than Raymond, who is the Lenny to a nerdy George who is a recurring character and seems to dislike Raymond). Then – a crisis! Something happens that requires him to go into his superheroic alter ego! But that means that his girlfriend will realise that Firestorm has turned up in a new town at the same time as Ronnie Raymond! His secret identity might be exposed!

There's a subplot here with Professor Stein also starting at the same university that Ronnie is going to, and being introduced to his presumed new supporting cast – an obnoxious teenage science prodigy who's already a grad student aged fourteen, and a brilliant young woman – like Stein, she has won a Nobel – in a wheelchair who is clearly being set up as a future love interest for him. This woman is quite likely inspired by Stephen Hawking – not only does she use a wheelchair, but she is a specialist in black holes, and she is given wobbly speech bubbles intended to represent slurred speech and says it's difficult for people to understand her (at the time this comic came out, Hawking still had some speech, but it was very slurred – he had a tracheotomy later that year which necessitated him using an assistive device to talk for him from that point on).

Sadly, though not unexpectedly for the medium and time period, there's also some casual ableism here, with Stein thinking to himself "She's wonderful. A mind like hers trapped in a body stricken by cerebral palsy. So unfair".

The action that interrupts the soap-operatics is the tie-in with Crisis #1, with Harbinger coming to collect Firestorm, as we saw in that issue. Here it goes into more detail, and there's a complication that gives an excuse for a brief action/fight scene. With Harbinger is a character I don't think I mentioned in the first of these essays, but who goes on to play an important part in Crisis. This is a villain called Psycho-Pirate, who has the ability to make people feel whatever emotion he wants them to by changing his expression when they look at him. Unfortunately, he makes Professor Stein terrified, so when Stein and Raymond merge as Firestorm and Harbinger tries to collect him, Firestorm fights back in terror and runs away until Psycho-Pirate can calm him again.

It's a comic with no weight to it at all, but it's a perfectly pleasant way to spend a few minutes, and I'm sure any twelve-year-olds in 1985 who were following Firestorm's monthly exploits enjoyed it. Not every creative work has to be a great work of art to be worthwhile. Sometimes, like here or Loving You, good enough is good enough.